Hieron (Greek Ἱερόν, Turkish Anadolu Kavağı) was a port, settlement, and fortress on the northern shore of the Asian coast of the Bosphorus. The upper castle of Hieron Castle (Turkish Yoros Kalesi) is located on the summit of a promontory around 800 m from the pier of Anadolu Kavağı. While the upper castle is open to the public, much of the lower fortifications are not accessible since they are in a military zone.

Yoros Castle from the Bosphorus

History

In antiquity, the name Hieron simply referred to its sanctuary (Greek hieron), thus also implying it was famous for being “the Sanctuary.” Various legends report that the Argonauts or Phrixos established a sanctuary (dedicated to the twelve gods or Poseidon) at Hieron. By the 1st century BC, it was the site of a temple dedicated to Zeus Ourios (“of the fair winds”). During this period, its ownership was disputed by Byzantium and Chalkedon. Since Hieron is where the Black Sea first comes into view, it was often considered the starting point of the Black Sea trade route, with Hieron being the point from which all Black Sea navigational charts took their measurements. There was a beacon at Hieron from a very early date, while a lighthouse was built later.

By Late Antiquity, Hieron was the site of the customs station and military base of the Bosphorus (similar to Abydos on the Dardanelles). According to Procopius, after Justinian took office, he set up a customs office in Hieron and Abydos, which excessively collected duties. During Justinian’s reign, the comes (“count”) of the straits of the Black Sea was based in Hieron during a war with Huns of Crimea. The comes at Hieron was later a subordinate of the droungarios (admiral) of the Fleet. The kommerkiarios (fiscal official) at Hieron are documented by seals dating between the 7th and 9th or 10th centuries. Empress Eirene reduced the kommerkia levied at Hieron and Abydos in 801, though these measures were reversed during the reign of Nikephoros I.

Due to its strategic significance, it was often the site of key historical events. John Chrysostom was briefly banished to Hieron in 403. In 764, the Black Sea froze, and wind blew icebergs towards the Black Sea coast and down the Bosphorus, hitting Hieron and the sea walls of Constantinople. Thomas the Slav, during his siege of Constantinople in 821-822, occupied the area to make sure no enemies were at his back and to attempt to gain local support. In 941, a large Rus’ fleet entered the Bosphorus to attack Constantinople. Even though they were thwarted, they continued attacking the region, ravaging the eastern shore of the Bosphorus. The Byzantine fleet came to Hieron and ambushed the Rus on the Bosphorus, destroying much of their fleet with Greek fire.

It is unclear when the current castle was built at Hieron, as there is no record of it being constructed. However, it is generally accepted that it was built by either Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180) or Michael VII Palaiologos (1261-1282). Once it was finished, it probably housed a large garrison. The Ottomans attacked the castle of Hieron (along with Chele and Astrabeke in western Bithynia) in 1304. Hieron was briefly occupied by the Ottomans in 1306, during which time its residences had to pay tribute. After the Genoese of Pera attacked a Venetian ship in the Aegean in 1328, a Venetian fleet came to Constantinople demanding reparations. When Pera refused to comply, the Venetians blocked the port of Hieron for 15 or 20 days, keeping ships from entering or leaving the Black Sea. The capture of a Byzantine fishing boat at Hieron was the first of a series of incidents that led to a military conflict between the Genoese and Byzantium in 1348. This led to the Genoese gaining control of Hieron, which was then known as Giro. In 1391, the Ottoman sultan Bayezid I captured Hieron and also had Anadolu Hisarı built by the shore of the Bosphorus to the south. Boucicaut, the marshal of France sent by Charles VI to aid the Byzantines in 1399, was unable to capture Hieron. Ruy González de Clavijo, who visited the court of Timur in the early 15th century, refers to Hieron as the “Turkish” castle, which he reports as being inhabited – while the “Greek” castle on the opposite shore of the Bosphorus was in ruin. He also claims that a chain was once pulled across the Bosphorus between the two castles. In 1414, the Genoese once again held Hieron, while the Ottoman captured it by the time of the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. During the reign of Bayezid II (1481-1512), Yoros Castle was repaired, and a mosque and bath were built in the castle. New fortifications were built along the shore by Murad IV in 1624. There was a Turkish quarter within the castle around the beginning of the 19th century, though it was later abandoned that century. The area of the castle was also used for military purposes during the Republic era, though the upper castle was later transferred to Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, while military lodgings were built in the 1980s.

Architecture

Hieron Castle (Turkish Yoros Kalesi) consists of an inner castle at the summit of the promontory and a large outer enclosure on the slope. It has an irregular plan, measuring between 60 and 130 m north to south and over 500 m east to west, while an additional 200-meter spur wall once extended down the slope towards the coast.

The upper inner castle, the main fortifications of the complex, has an irregular square plan. Its upper gate – the main entrance of the castle – is flanked by two massive circular towers that are 20 m tall and less than 7 m apart. There were two ditches in front of the main gate to the east. The gateway, which is now walled up, has a large square plan in the castle’s interior, with staircases on each side. The gate has brick vaulting and was protected with a portcullis.

The circular towers are accessed at the ground level from arched openings. Each tower has a tall cruciform chamber with a brick dome and arches. The towers probably had wooden floors under their loopholes, which are around 8 m above the ground. The masonry of the gate and towers consists of alternating bands of brick and stone (with six or seven bands of brick and stone), though spolia was extensively used as well. The gate has a broken reused door frame with a richly decorated architrave. The spolia of the towers includes numerous Late Antique impost capitals. Each tower also has two marble slabs with crosses and tetragrams.

There is one round tower on the southern curtain wall of the upper castle. Its northern curtain wall has no towers (as is also the case for the northern wall of the outer enclosure), probably due to the precipitous northern side of the castle. The eastern and southern curtain walls were reinforced by a series of blind arches that could have supported a wide wall-walk.

The western wall between the upper castle and the outer enclosure has two square towers on each end and two round towers in the middle. The northern round tower has a Greek brick inscription that is no longer legible.

The outer enclosure, now largely in a military area, is only partially preserved. It had smaller round towers at intervals of 80 meters or more, though there were none on its northern side, except on the northwestern corner. A gate flanked by two towers, now mostly in ruins, was on the southwestern corner of the outer enclosure walls. A spur wall connected to the gateway continued down towards the shore. A landing site on the shore was also secured by other fortifications that were still visible in older illustrations.

The date of the castle is controversial, though it is generally argued that it was built by either Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180) or Michael VII Palaiologos (1261-1282). One reading of a marble slab over its main gate (now at Istanbul Archaeological Museums) has been used to support a Palaiologan date, while a comparison to the Blachernai walls has been made to argue for a Komnenian date. It is also possible that its earliest phase is Komnenian, while later additions were made during the Palaiologan era (such as the partition wall with four towers, which created the upper castle). The brickwork of the inscription on one of the round towers of this partition wall is arguably Palaiologan. Regardless of its date, several repairs have been recorded, including by the Genoese and Ottomans. A lost Latin inscription, dating to the 14th or 15th century, documents repairs made by the Genoese.

The 2010-2015 excavations made discoveries about the settlement inside the castle. While there are no traces of the mosque or bath added during the Ottoman era, excavations uncovered finds that largely date to the Ottoman era. Numerous Late Byzantine and Early Ottoman pottery sherds found on site suggest the continuity of life at Hieron from the Byzantine to the Ottoman era. The excavations made marble, ceramic, and glass finds, as well as metal artifacts, such as horseshoes, nails, and a key. While some Late Byzantine coins were discovered, most of the coins found at the site date to the Ottoman era. The excavations also uncovered foundations of buildings (including evidence of a kiln), terracotta pipes, and remains of a paved road.

Slabs and Inscriptions from Hieron Castle

Tetragrams from the marble slabs of the left and right towers of the main gate

ΦC XY ΦC ΠΑ or ΦC XC ΦC ΠC

Φώς Χριστού φαίνει πάσιν /Φῶς Χριστὸς φῶς πᾶσιν

“Light of Christ shines for all”

IC XC ΝΗ ΚΑ

Ι(ησοῦ)ς Χ(ριστὸ)ς νηκᾷ

“Jesus Christ is Victorious”

Marble slab at Istanbul Archaeological Museums

Stolen from the back side of the main gate of the upper castle in 2010

Tetragram ΑΠΜΣ (or possibly ΔΠΜΣ)

Ἀρχὴ Πίστεως Μυστηρίου Σταυρός

“The beginning of faith is the Cross of mystery”

Lost marble slab with four betas (From Toy, 1929)

βασιλεὺς βασιλέων, βασιλεύων βασιλευόντων

“King of Kings, Ruling over Rulers”

A recorded 14th-15th century Latin inscription, though now lost, documents the Genoese administration of Hieron.

FORTALITIVM PROMONTORII SACRII INIVRIA TEMPORVM DIRVTVM VINC. LERCARI CIVIS IANVENSIS PROPRIIS EXPENSIS RES...TVIT ET AD MARE VSQVE PROTRAXIT A... M...

The fortress of the sacred promontory was damaged and dismantled over time. Vincenzo Lercari, a citizen of Genoa owns the expenses of its rebuilt and extension until the sea

Illegible two-line Greek brick inscription from the western wall of the upper castle

View of upper castle's western wall and tower

Blind arches that supported the wall-walk

Western wall of upper castle

Upper castle and southeastern tower of outer enclosure

Ruins of southeastern tower of outer enclosure

Northern wall of outer enclosure

Southern tower of outer enclosure

Northwestern tower of outer enclosure

Tower from the Blachernai Walls built by Manuel I Komnenos

Tower of the Upper Castle

Comparisons have been made with the masonry of towers of the Komnenian walls and Hieron Castle

Aerial photo by Kadir Kir

Byzantine fleet defeats the Rus near Hieron in 941

From Madrid Skylitzes (f. 130r) at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica

From A Synopsis of Byzantine History by John Skylitzes

In the month of June, fourteenth year of the indiction, there was an assault on the city by a Russian fleet of ten thousand ships. The patrician Theophanes, the protovestiarios, sailed out against them with the fleet and tied up at the Hieron, while the enemy was moored off the Lighthouse and the adjacent shore. Waiting for the right moment [Theophanes] attacked in full force and threw them into disorder. Many of their vessels were reduced to cinders with Greek fire while the rest were utterly routed.

Giro (Hieron) from the Portolan chart of the Black Sea

Perrino Vesconte (1321)

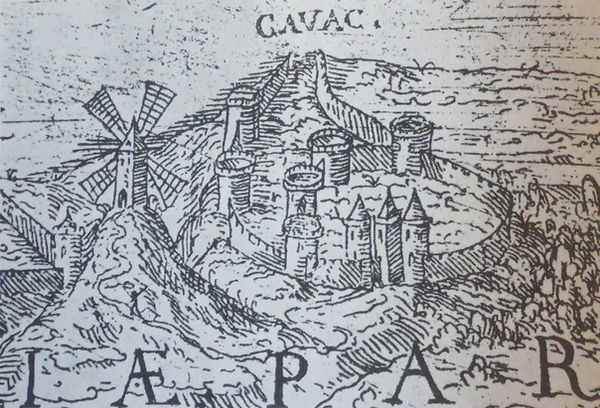

Cavac (Anadolu Kavağı) from Bosphorus map

From Heberer von Bretten (1610)

“View of the Bosphorus and the Black Sea”

From Cornelis de Bruijn (1714)

From Histories by Herodotus

Darius continued his march from Susa to Chalcedon on the Bosphorus, where the bridge was, and then took ship and sailed to the Kyanean rocks, those rocks which according to the Greek story used to be changing their position. And seated at Hieron he looked out over the Pontus - a sight indeed worth seeing.

“View of the Opening to the Black Sea, from the north eastern extremity of the Thracian Bosporus, with the site of the Temple of Jupiter Urius”

From Edward Daniel Clarke (1810)

From Dionysius of Byzantium

After Scletrina are the "Red Chalk" promontory, named from its likeness to the color, and the nearby house of a certain admiral, and a rough and sheer coastline with an east-facing cliff; around that same place is a stretch of sea punctuated by reefs, and the Hieron, which is located exactly facing the Asian Hieron. They say that this was the place where Jason sacrificed to the Twelve Gods. These Hiera are small towns sited next to the mouth of the Pontus; there is also a temple to the Phrygian goddess, a famous holy place and a cult open to all.

A Castle on the Bosphorous

Achille Etna Michallon (1816)

“Entrance to the Bosphorus from the Black Sea”

From R. Walsh, by T. Allom (1836)

The Bosphorus from the fortress above Anadolu Kavagi on the Asian shore

Giuseppe Schranz (ca. 1835) V&A

“Entrance to the Black Sea (From the Giants Grave)”

From J. Paroe, by W.H. Bartlett (1838)

From The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor

In the same year, starting in early October, there was very bitter cold, not only in our land, but even more so to the east, the north, and the west, so that on the north coast of the Pontos to a distance of 100 miles the sea froze from the cold to a depth of thirty cubits…All this ice was snowed upon and grew by another twenty cubits, so that the sea became indistinguishable from land: upon this ice wild men and tame animals could walk from the direction of Chazaria, Bulgaria, and other adjoining countries. In the month of February of the same 2nd indiction this ice was, by God's command, split up into many different mountain-like sections which were carried down by the force of the winds to Daphnousia and Hieron and, by way of the Straits, reached the City and filled the whole coast as far as the Propontis, the islands, and Abydos. Of this I was myself an eyewitness, for I climbed on one of those [icebergs] and played on it together with some thirty boys of the same age.

“The Bosphorus (Opposite the Genoese Castle)”

From J. Paroe, by W.H. Bartlett (1838)

By the Late Byzantine era, there was another castle on the opposite shore of the Bosphorus; this site was once known in antiquity as Sarapieion (medieval Hieron and Ottoman Rumelikavağı). The Monastery of St. Panteleimon was located on the promontory to the south (around Yuşa Tepesi).

From González de Clavijo

After dinner they continued their voyage, and soon afterwards they passed two castles on hills near the sea, the one being called “El Guirol de la Grecia,” and the other “El Guirol de la Turquia,” the former being in Greece, and the other in Turkey. The Grecian tower is ruined and deserted, but the Turkish one is inhabited. In the sea, between these two castles, there is a tower surrounded by the water; and at the foot of the Turkish castle there is a tower built on a rock, with a wall connecting them. Formerly a chain was stretched from one tower to the other, and when the land on both sides belonged to the Greeks, these castles were used to guard this strait; and any vessel passing from the greater sea to Pera and Constantinople, or from Pera to the sea, was stopped by a chain stretched across from one castle to the other, and was thus detained until the dues were paid.

Jules Laurens (1846)

From Le Magasin pittoresque

By Jules Laurens (1879)

Basile Kargopoulo (c. 1870s)

Basile Kargopoulo (c. 1870s)

Guillaume Berggren (c. 1880s)

From Toy (1929)

From Gabriel (1943)

Kosmas komes of Hieron (eighth/ninth c.)

John imperial spatharokandidatos and kommerkiarios of Hieron and Pontos (tenth/eleventh c.)

From The Secret History by Procopius

That was how this tyrant treated men in the service. I turn now to state what he did to merchants, sailors, laborers, and ordinary craftsmen, and through them to all others. There are straits on either side of Byzantion, one in the Hellespont between Sestos and Abydos, another at the mouth of the Black Sea, at a place called Hieron. In the Hellespont straits one could hardly say that there was a public customs station; rather, an official was sent out by the emperor and stationed at Abydos who inquired whether any ships were bringing weapons to Byzantion without imperial authorization, and also whether anyone was sailing out from Byzantion without the proper documents bearing the seals of the men charged with that function (for it was not permitted for anyone to depart from Byzantion without the permission of those men, who worked for the office of the magister; as he was called). He also extracted a fee from the owners of the ships, not anything that they would really feel but merely a form of compensation that was demanded by the holder of the office in exchange for providing this service. The one who was sent to the opposite straits, however, had always received his salary from the emperor and his job was to inquire carefully into the matters that I just mentioned as well as to ensure that nothing was being exported to the barbarians settled around the Black Sea, nothing, that is, of those articles whose export from Roman territory to foreign enemies was prohibited. And, in fact, this man was forbidden from accepting payment from those sailing in this direction. But when Justinian became emperor, he established a customs station in both straits to which he regularly sent out two salaried officials. While he did provide them with their own salaries, he also bid them to use any means at their disposal to bring in as much revenue as they could for him from this source. And they, wanting nothing more than to prove their devotion to him, stole from merchants sailing by the full cash value of their entire cargo.

Plan from Gabriel

References

Belke, Klaus. Bithynien und Hellespont (Tabula Imperii Byzantini 13)

Foss, C. & Winfield, D. Byzantine Fortifications: An Introduction

Eyice, S. Bizans Devrinde Bogazici

Gabriel, A. Châteaux Turcs du Bosphore

Toy, S. The Castles of the Bosporus

Kontogiannis, N. Byzantine Fortifications: Protecting the Roman Empire in the East

Saglam, H. Urban Palimpsest at Galata and an Architectural Inventory Study for the Genoese Colonial Territories in Asia Minor

Kazhdan, A. (ed) Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

Eyice, S. “Yoros Kalesi” (İstanbul Ansiklopedisi)

Sağlam, H. “Şile and its Castle: Historical Topography and Medieval Architectural History”

Moren, A. “Hieron: The Ancient Sanctuary at the Mouth of the Black”

Yalçın, A. “Yoros Kalesi 2010 Yılı: Kazı, Koruma-Onarım Çalışmaları”

Yalçın, A. “Anadolu Kavağı, Yoros Kalesi 2012 Yılı Kazı Çalışmaları”

Yalçın, A. “Anadolu Kavağı, Yoros Kalesi 2013 Yılı Kazı Çalışmaları”

Türkmenler, F. & Çepnioğlu, Ö. “Yoros Kalesi Kazılarında Bulunan Osmanlı Dönemi Sikkeleri”

Kurugöl, S. & Tekin, Ç. “İstanbul’da Bizans Dönemi Yoros Kalesi Üzerine Bir İnceleme”

Primary Sources

Moren, A. “Hieron: The Ancient Sanctuary at the Mouth of the Black”

Kaldellis, A. (trans.) Prokopios: The Secret History: With Related Texts

Greatrex, G. & Mango, C. (trans.) The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor: Byzantine and Near Eastern History, AD 284-813

Wortley, J. (trans.) John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811-1057: Translation and Notes

Markham, C. (trans.) Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy González de Clavijo to the court of Timour

Resources

Hieron/Yoros Castle Album (Byzantine Legacy Flickr)

Portolan charts of the Black Sea by Perrino Vesconte (Medea Chart)